November 24, 2020

From Field to Scone: K-State Grain Scientists Bring Life to 4-Hers' Projects

On an otherwise routine Thursday night in mid-November, about 40 Kansas 4-H members were transported by computer screen to a flour mill and baking lab on the Kansas State University campus.

Such is the life of online learning during a global pandemic, though this trip was symbolic. The one-hour journey marked the kickoff of a program – called Bring Your 4-H Projects to Life -- that aims to connect youth to college and career opportunities related to their interests.

“Not only does this provide an additional opportunity for youth to learn about their 4-H projects, but it is also purposeful programming to enhance our mission toward career readiness,” said Lindsey Mueting, a 4-H youth development agent in McPherson County.

Mueting and Sarah Maass, a 4-H youth development agent in the Central Kansas Extension District, developed the series to run on the second Thursday of each month. Each month’s program will connect youth to professionals currently working in an area related to one of 34 projects offered by Kansas 4-H.

“We are making connections with new people and using our amazing resource of the university to bring college and career ideas and opportunities to our 4-H youth,” Mueting said.

On its maiden voyage, the program took the youth and their parents to the inner-workings of the K-State Department of Grain Science and Industry, where faculty members walked them through the life of a kernel of wheat as it is taken from a farm field, processed into flour, made into dough, and formed into scones for baking.

Jason Watt, the Buhler Instructor of Milling at K-State, explained the anatomy of a wheat kernel and explained how three parts – the bran, germ and endosperm – are all needed for whole wheat flour.

He used simple equipment to show the youth how a kernel is first cleaned, then crushed to its finest form. The process he demonstrated was tedious when done by hand; larger, more automated equipment gets the job done in just a fraction of the time.

“How long does it take to process one pound of flour?” one youth asked.

On a small scale – such as what Watt demonstrated – the answer is 30 minutes. But, he said: “The average wheat flour mill will make 750,000 pounds of flour a day, to upwards of 1.2 million pounds of flour a day. If you’re talking about one pound of flour…well, probably just a few seconds.”

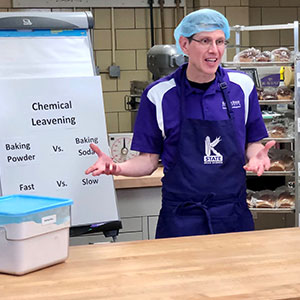

Up the hallway, baking science instructor Aaron Clanton, was preparing dough to make scones. As the online learning shifted to his baking lab, he began with a chemistry lesson on the important differences associated with using baking powder or baking soda in recipes.

“Both are leavening agents which cause baked goods to rise,” he said, “but they are not created equal.”

Clanton then showed how each product reacted to cold water, hot water and vinegar. Baking powder, which contains both an acid and an alkaline component, bubbled as it interacted with each ingredient. Baking soda, which does not contain acid, only reacts when it is combined with an acid, such as vinegar.

The lesson became more clear when Clanton showed examples of scones made with each ingredient. The scones with baking powder rose to a good height and color with fluffy air pockets in the middle. The ones without baking powder were flat and crumbly.

“There is a lot of science involved in baking,” said Clanton, a 4-H member as a youth. “It’s a very rewarding thing to learn about. It’s something you can learn about in your 4-H foods project, and as you go on, you’ll learn that the food industry relies on a lot of science to make products.”

Each of the youth received baking ingredients and a recipe to make their own scones at home. In the week following the online lesson, they were encouraged to post pictures, videos and description of their own scones online, Mueting said.

“The pandemic definitely brought about a new way of thinking for educators and our families,” Mueting said. “I don't think something like this would have come about a year ago, but there are some changes we made that I hope we as Extension professionals don't ever lose. Stepping outside our comfort zones to collaborate between units on projects has been a blessing that hopefully extends well past the pandemic.”

Gordon Smith, head of the Department of Grain Science and Industry, said the interaction with the 4-H youth was mutually beneficial. He hopes some of those kids will develop an early connection to the university and eventually choose to get their own education on campus.

“Extension agents are part of our family,” Smith said. “We’re all committed to the education of students at any age. And we believe that you guys (the 4-H youth) are the future.”

For more information on upcoming lessons through Bring Your 4-H Project to Life, interested persons can contact Mueting at Lmueting@ksu.edu; or Maass at semaass@ksu.edu.